There are different aspects to Big Society which require different skills and resources to deliver them. Community groups will need to have the capability to take advantage of opportunities to become more involved in public service reform, to increase social action and hold the state to account through open government.

Many of the skills, expertise and resources that VCS groups need are the same as they have always been; setting up and running groups, effective governance, communications, fundraising, strategic planning, using ICT etc. But what’s new? If Big Society offers something new then there are skills and resources that are different which the voluntary and community sector needs?

Here are some thoughts on the sorts of skills and capacity we will need to develop within the not-for-profit sector to grow the Big Society….

Innovation

Developing creative solutions to the challenges we face is nothing new for the sector, but it will be increasingly important for these skills to come to the fore. Unlike the private sector and public sector, there is relatively little investment in community sector innovation and support to ensure the learning from new approaches is captured, distilled and disseminated. It is crucial that community sector innovation is more systematically supported and learning from it ploughed back in to supporting adoption and adaptation. We cannot afford to continue to let the learning, skills and enthusiasm to be lost. The neighbourhood renewal agenda pumped £bns into community-led regeneration and social innovation, but (as John Houghton and I have argued in our article on the lessons from the Community Empowerment Programme) much of this investment has gone to waste as the government lost interest in it.

There is so much innovative practice within the community sector that others can learn from, but until we recognise it and support it more consistently, we will fail to capitalise on the full potential it offers. I welcome the increased emphasis organisations like NESTA are placing on innovation in the public realm and I hope this continues as I believe it is crucial to our future prospects.

Creative collaboration

The acknowledgement that the political and economic climate requires us to change is stimulating all sorts of discussions and collaboration. New partnerships – often unlikely or unusual – are being formed and people appear to be far more prepared to consider radically different things as a result of the financial climate. Although the drivers for this collaboration may be negative, I regard the opportunities that it is stimulating as a positive development.

However this isn’t simply about working with different partners. It is also about transforming the way that we work. Clay Shirky’s seminal book ‘Here Comes Everybody’ talks about ‘organising without organisations’ and how technological developments are fundamentally changing the way we (can) work together in groups for productive purpose. We don’t know yet what the full implications of social tools like Flickr, Twitter and Ushahidi will be on society, but they will clearly make a great difference to how we self organise and collaborate and therefore have huge significance for the future of social action.

Although I think many of us in the VCS have been relatively slow to explore the implications and potential of social technology, the most obvious benefit I can see is the chance to drastically enhance the way we interact with and involve our beneficiaries. The process of creative collaboration and using these new tools will require a new set of skills and a preparedness to change.

Community organising

The government’s national programme to support the training of 5,000 community organisers has already generated a lot of attention (and I have written before about my take on the programme’s origins and potential). The process of community organising, whilst not new, is far less widely practiced than related approaches like community development, and will require new skills and expertise, if we are take full advantage of the opportunities it presents.

Of course the government’s programme is only part of the story as many areas are already using community organising or planning to do so. Whether or not we develop community organising skills through the Locality-led programme or not is something of an irrelevance. The more substantial point is the potential to add community organising to the range of tools and skill-set we have at our disposal to reform public services, hold the state to account and increase social action.

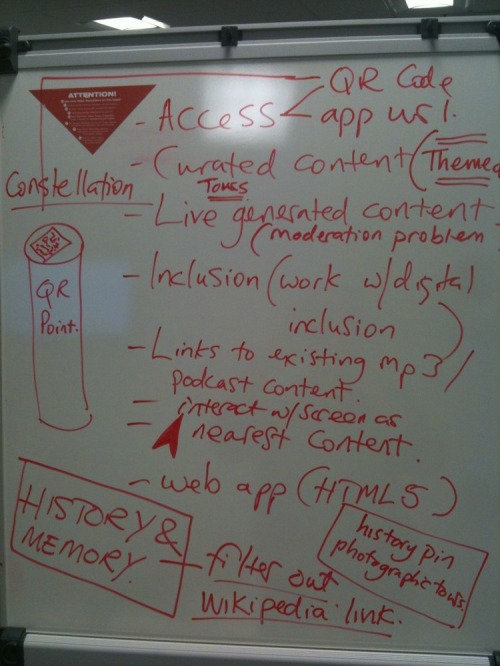

Open data

The government’s commitment to make data available to the public is perhaps Big Society’s forgotten theme. The potential for VCS groups to use this information more effectively is significant, but to do so requires new tools and new skills. There is currently too little emphasis on creating open data tools designed with citizens and the VCS in mind. Without these tools we cannot hope to use it effectively and it will actually make it harder, not easier, for us to hold the state to account and to use data to improve and design more responsive public services.

Resilience and asset mapping

Something we are increasingly interested in at Urban Forum is how we can develop the skills and methodologies to better identify and mobilise resources within our communities. Only if we understand what we have can we hope to harness these assets and resources to achieve our aims. People, land, buildings, skills, interests and expertise reside in all our communities and I’m certain that they could be better directed and organised to improve and strengthen resilience and increase community action. The work that Tessy Britton has been doing, through her Travelling Pantry, and our own work with CLES on community resilience, offer a way forward, but we have a long way to go.

Equalities and inclusion

One of the greatest risks to Big Society is that the opportunities it might create are not taken up equally by different groups and areas. If we fail to recognise the unequal capacity of particular groups to use new opportunities like Community Rights, we will exacerbate inequality and jeopardise any prospect of positive change. The VCS has a long and proud history of fighting for the weak and vulnerable in our society, but recent years have seen a growing inequality within the sector. The wealth and power concentrated in the hands of the largest not-for-profit organisations poses a risk to more marginalised groups playing a fuller role in civil and civic life. We must acknowledge this inequality and find ways to support partnership working – on an equal footing –between larger and smaller groups.

The success of those who shout the loudest for their cause comes at a price – often the further marginalisation of those who already lack power and influence. Parochialism and vested interest will lead to an increasing gulf between the sector’s haves and have-nots and we must honestly appraise its impact. There is so much potential for the sector as a whole to deploy its resources more equitably and efficiently in order to achieve our broad ambitions to tackle inequality and exclusion.

Beginning to grow our skills and capacity

These are some of the skills that I believe we will need to develop in order to capitalise on the emerging opportunities to affect positive social change through Big Society. It is not intended to be comprehensive and there are many other things we will need in order to be successful. Nor am I suggesting that everything that the government is doing is consistent with their big Big Society rhetoric. However, my hope is that we are able to grasp the opportunities that might emerge and use them to their maximum effect. We must start thinking about the skills and knowledge we might need to do this and from there begin developing strategies and plans to build our own capacity in the future.

Toby Blume

Chief Executive

Urban Forum

Twitter: http://twitter.com/tobyblume/

Facebook: http://tiny.cc/UFonFB